WRETCH’S

WILL WESSEL

Q&A

GN: Your practice centers on the concept of “social armor.” When did you first recognize that textiles and later painting could function as a form of protection, empowerment, and psychological assurance for the wearer?

WW: Clothing is nonverbal communication. I think there is a lot of connotation and baggage with most clothing. Paint on clothing today is mostly a newer concept. Rather than hiding in “classic” boring clothes, the wearer can be seen without being boxed into a specific genre.

GN: With a background in biology, you often reference ideas such as sovereignty and phenotypic plasticity. How do these scientific principles inform the way you shape garments and consider the individuality of the people who inhabit them?

WW: Most clothing is finite in terms of production. With paint you don’t have to wait on the limitations of traditional production. It’s theoretically more infinite and democratic in the final product allowing the individual to be dressed appropriately for more occasions based on very specific preferences.

GN: You’ve long collected vintage garments, how has your understanding of vintage evolved from its historical lineage to your own interpretations of “current trends” and what meaning does it hold in your work today?

WW: Historically a lot of clothing was created and decorated by hand. We’ve had hippy moments here and there but today whats currently trendy is a lot of machine made algorithm slop. Drinking this gruel aid can help you fit in certain groups but boxes you out of real potential. Rather than waiting on machines, other people, and trends I hope to create a sense of sovereignty for the wearer.

GN: Studying the origins of vintage and repurposing clothing with art, how has that emotional shift influenced your move toward creating objects that aim to comfort, protect, or reframe rather than replicate?

WW: There’s plenty of well made beautiful things in the past worth replicating and referencing but our world is different today. The needs for comfort and protection are more psychological than physical due to advances in technology. Feeling unseen or rejected is much more common a condition than potential frostbite.

GN: You’ve described painting as a liberating alternative to traditional garment production. What creative possibilities does painting afford that textile design alone cannot, and how has it expanded your visual language?

WW: The imperfections of paint are charming. Paint can add texture, making something looking more 3D than 2D. In a world that feels more digital, mechanical, fake, and monotone there’s something very human, emotional, and raw about it.

GN: Your work gives wearers choices how much to reveal or conceal, when to speak visually and when to remain quiet. What do you hope individuals experience or better understand about themselves when navigating those options within your pieces?

WW: Besides the paint there is a lot of black. If you don’t want to be bothered this is obviously a good choice. The wearer noticing when they feel safe being seen can guide them to a sense of community. In the meantime pragmatically there’s black until they find those places.

GN: Fashion’s definition of luxury is often shaped by scarcity, access, and infrastructure. How do you envision your approach contributing to a more democratic understanding of beauty, craftsmanship, and self-expression?

WW: Really anyone can paint clothing. Obviously doing it well requires skill, practice, and taste. I hope the wearer is inspired to create a feeling of luxury in any circumstance. This might mean they paint their own clothing, or have a friend do it. It might mean they take a cooking class. There are plenty of amazing stores or restaurants but I don’t want anyone to feel excluded from the possibility of luxury and beauty on their own terms.

GN: Your practice merges history, emotion, science, and personal narrative. As you look ahead, where do you see your work moving next? What new terrain, creative or conceptual are you most compelled to explore?

WW: It’s exciting to see what materials can combine to create different effects. A science lab should probably be more controlled than an art studio. Some of my best work is on accident or a random hunch that worked. Maybe become a bit more of a mad scientist and involve more mad scientists as well.

GN: You’ve said your overarching aim is to make wearers feel “special and safe.” As your craft evolves, what does an ideal future look like one in which clothing and art genuinely offer a sense of belonging, protection, and dignity?

WW: I think a lot of people want to be seen but don’t know the best way to do it. Negative attention or “rage bait” is a very popular marketing concept but I think that’s making the world a much worse place. Ideally one can be seen for who they are, add beauty to the world and be comfortable enough to share helpful perspectives without being dismissed based on appearance.

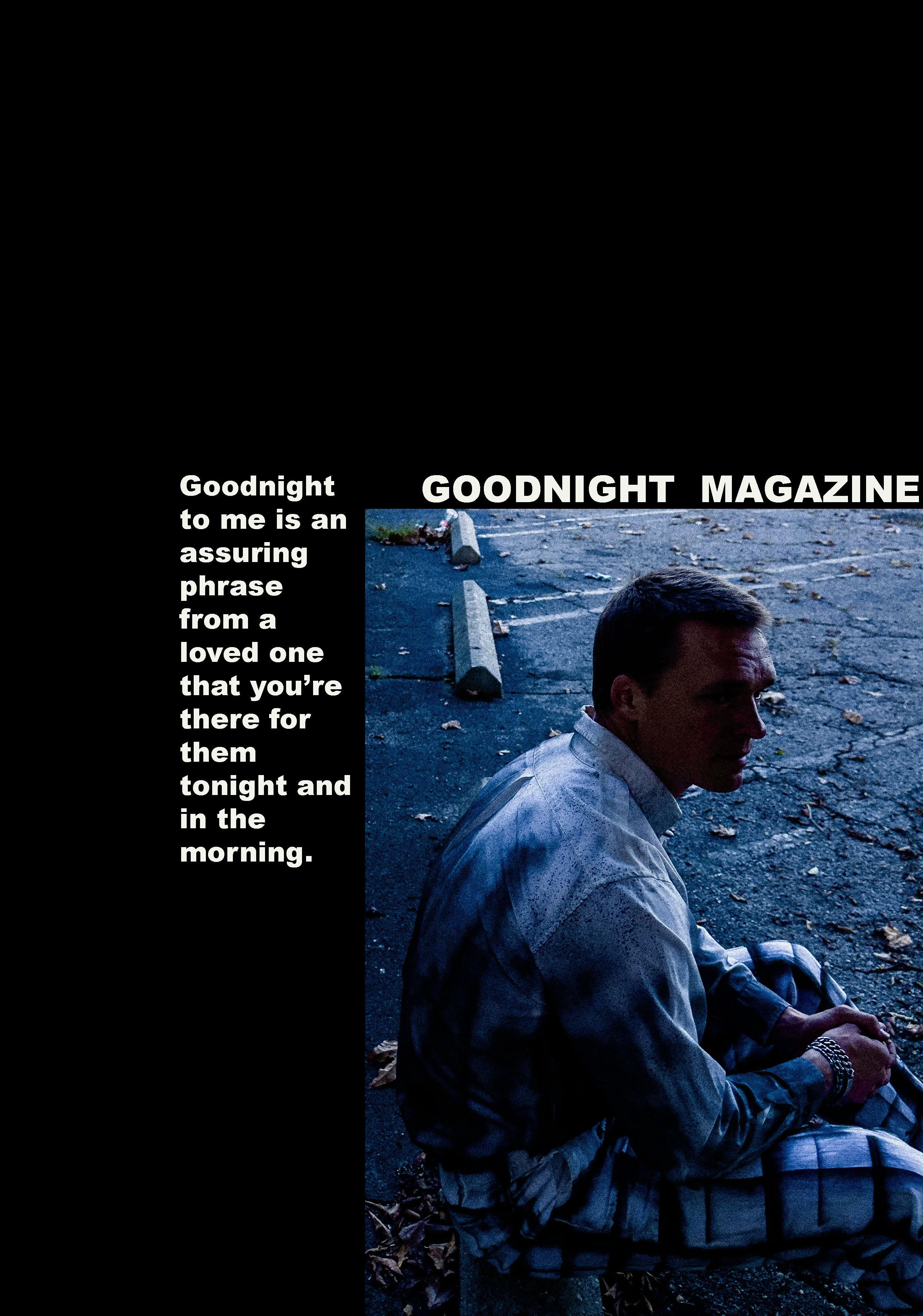

GN: What does the term Goodnight mean to you?

WW: Goodnight to me is an assuring phrase from a loved one that you’re there for them tonight and in the morning.

Images courtesy of photographer Mi

Stylist Kimberly Goodnight

Groomer Lisa Sasson